|

Blue is a 1993 French film written, produced, and directed by the acclaimed Polish director Krzysztof Kieslowski. Blue is the first in the Three Colors trilogy, themed on the French Revolutionary ideals; it is followed by White and Red. According to Kieslowski, the subject of the film is liberty, specifically emotional liberty, rather than its social or political meaning. Set in Paris, it depicts Julie, a woman whose husband and child are killed in a car accident. Suddenly set free from her familial bonds, Julie attempts to cut herself off from everything and live in isolation from her former ties, but finds that she cannot free herself from human connections.

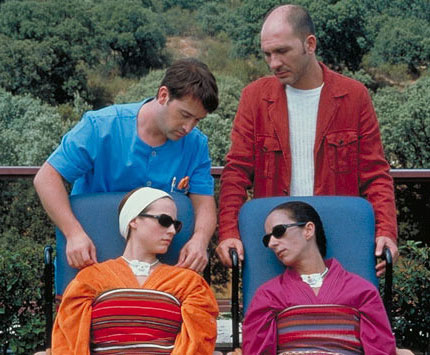

Julie, wife of the famous composer Patrice de Courcy, must cope with the death of her husband and daughter in an automobile accident she herself survives. While recovering in the hospital, Julie attempts suicide by overdose, but cannot swallow the pills. After being released from the hospital, Julie closes up the house she lived in with her family and takes an apartment in Paris without telling anyone, or keeping any clothing or objects from her old life, except for a chandelier of blue beads that presumably belonged to her daughter. For the remainder of the film, Julie disassociates herself from all past memories and distances herself from former friendships, as can be derived from a conversation she has with her mother who suffers from Alzheimer’s disease and believes Julie is her own sister Marie-France. She also destroys the score for her late husband's last commissioned, though unfinished, work: a piece celebrating European unity, following the end of the cold war. Snatches of the music haunt her throughout the film.

She reluctantly be friends an exotic dancer who is having an affair with one of the neighbors and helps her when she needs moral support. Despite her desire to live anonymously and alone, life in Paris forces Julie to confront elements of her past that she would rather not face, including Olivier, a friend of the couple, also a composer and former assistant of Patrice's at the conservatory, who is in love with her, and the fact that she is suspected to be the true author of her late husband's music. Olivier appears in a TV interview announcing that he shall try to complete Patrice's commission, and Julie also discovers that her late husband was having an affair. While both trying to stop Olivier from completing the score and finding out that her husband's mistress was, she becomes more engaged despite her own efforts not to be. She tracks down Sandrine, Patrice's mistress, and finds out that she is carrying his child; Julie arranges for her to have her husband's house and recognition of his paternity for the child. This provokes her to begin a relationship with Olivier, and to resurrect her late husband's last composition, which has been changing according to her notes on Olivier's work. Olivier decides not to incorporate the changes suggested by Julie, stating that this piece is now his music and has ceased to be Patrice's. He says that she must either accept his composition with all its roughness or she must allow people to know the truth about her composition. She agrees on the grounds that the truth about her husband's music would not be revealed as her own work.